10 Efficient AI

Efficiency in artificial intelligence (AI) is not simply a luxury; it is a necessity. In this chapter, we dive into the key concepts that underpin efficiency in AI systems. The computational demands placed on neural networks can be daunting, even for the most minimal of systems. For AI to be seamlessly integrated into everyday devices and essential systems, it must perform optimally within the constraints of limited resources, all while maintaining its efficacy. The pursuit of efficiency guarantees that AI models are streamlined, rapid, and sustainable, thereby widening their applicability across a diverse array of platforms and scenarios.

Recognize the need for efficient AI in TinyML/edge devices.

Understand the need for efficient model architectures like MobileNets and SqueezeNet.

Understand why techniques for model compression are important.

Get an inclination for why efficient AI hardware is important.

Appreciate the significance of numerics and their representations.

Appreciate that we need to understand nuances of model comparison beyond accuracy.

Recognize efficiency encompasses technology, costs, environment, ethics.

The focus is on gaining a conceptual understanding of the motivations and significance of the various strategies for achieving efficient AI, both in terms of techniques and a holistic perspective. Subsequent chapters will dive into the nitty gritty details on these various concepts.

10.1 Introduction

Training models can consume a significant amount of energy, sometimes equivalent to the carbon footprint of sizable industrial processes. We will cover some of these sustainability details in the AI Sustainability chapter. On the deployment side, if these models are not optimized for efficiency, they can quickly drain device batteries, demand excessive memory, or fall short of real-time processing needs. Through this introduction, our objective is to elucidate the nuances of efficiency, setting the groundwork for a comprehensive exploration in the subsequent chapters.

10.2 The Need for Efficient AI

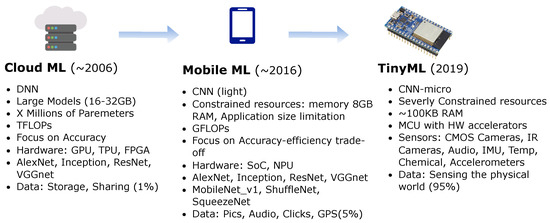

Efficiency takes on different connotations based on where AI computations occur. Let’s take a brief moment to revisit and differentiate between Cloud, Edge, and TinyML in terms of efficiency.

For cloud AI, traditional AI models often ran in the large—scale data centers equipped with powerful GPUs and TPUs (Barroso, Hölzle, and Ranganathan 2019). Here, efficiency pertains to optimizing computational resources, reducing costs, and ensuring timely data processing and return. However, relying on the cloud introduced latency, especially when dealing with large data streams that needed to be uploaded, processed, and then downloaded.

For edge AI, edge computing brought AI closer to the data source, processing information directly on local devices like smartphones, cameras, or industrial machines (Li et al. 2020). Here, efficiency encompasses quick real-time responses and reduced data transmission needs. The constraints, however, are tighter—these devices, while more powerful than microcontrollers, have limited computational power compared to cloud setups.

Pushing the frontier even further is TinyML, where AI models run on microcontrollers or extremely resource-constrained environments. The difference in performance for processors and memory between TinyML and cloud or mobile systems can be several orders of magnitude (Warden and Situnayake 2019). Efficiency in TinyML is about ensuring models are lightweight enough to fit on these devices, use minimal energy (critical for battery-powered devices), and still perform their tasks effectively.

The spectrum from Cloud to TinyML represents a shift from vast, centralized computational resources to distributed, localized, and constrained environments. As we transition from one to the other, the challenges and strategies related to efficiency evolve, underlining the need for specialized approaches tailored to each scenario. Having underscored the need for efficient AI, especially within the context of TinyML, we will transition to exploring the methodologies devised to meet these challenges. The following sections outline at a high level the main concepts that we will dwelve into deeper at a later point. As we delve into these strategies, we will demonstrate the breadth and depth of innovation needed to achieve efficient AI.

10.3 Efficient Model Architectures

Choosing the right model architecture is as crucial as optimizing it. In recent years, researchers have explored some novel architectures that can have inherently fewer parameters while maintaining strong performance.

MobileNets: MobileNets are a class of efficient models for mobile and embedded vision applications (Howard et al. 2017). The key idea that led to the success of MobileNets is the use of depth-wise separable convolutions which significantly reduce the number of parameters and computations in the network. MobileNetV2 and V3 further enhance this design with the introduction of inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks.

SqueezeNet: SqueezeNet is a class of ML models known for its smaller size without sacrificing accuracy. It achieves this by using a “fire module” that reduces the number of input channels to 3x3 filters, thus reducing the parameters (Iandola et al. 2016). Moreover, it employs delayed downsampling to increase the accuracy by maintaining a larger feature map.

ResNet variants: The Residual Network (ResNet) architecture allows introduced skip connections, or shortcuts (He et al. 2016). Some variants of ResNet are designed to be more efficient. For instance, ResNet-SE incorporates the “squeeze and excitation” mechanism to recalibrate feature maps (Hu, Shen, and Sun 2018), while ResNeXt offers grouped convolutions for efficiency (Xie et al. 2017).

10.4 Efficient Model Compression

Model compression methods are very important for bringing deep learning models to devices with limited resources. These techniques reduce the size, energy consumption, and computational demands of models without a significant loss in accuracy. At a high level, the methods can briefly be binned into the following fundamental methods:

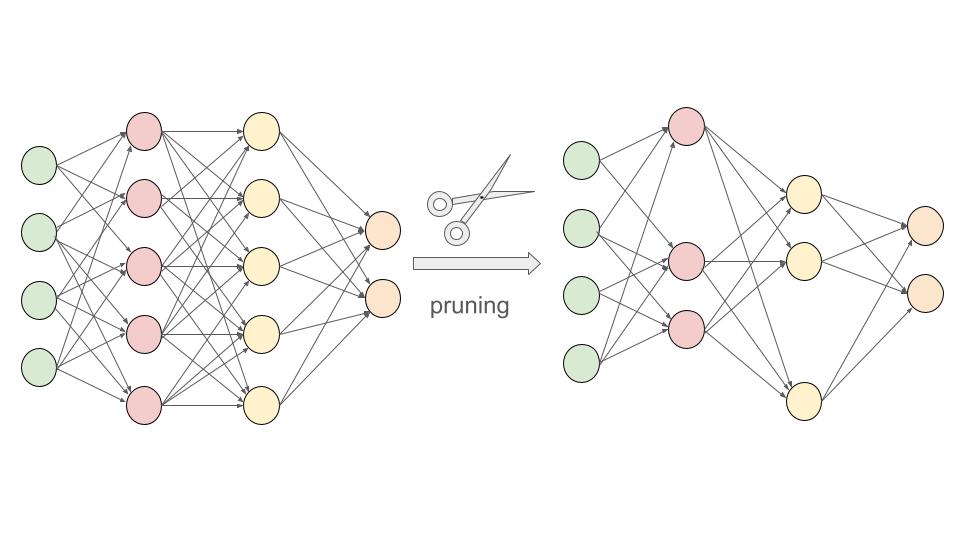

Pruning: This is akin to trimming the branches of a tree. This was first thought of in the Optimal Brain Damage paper (LeCun, Denker, and Solla 1989). This was later popularized in the context of deep learning by Han, Mao, and Dally (2016). In pruning, certain weights or even entire neurons are removed from the network, based on specific criteria. This can significantly reduce the model size. There are various strategies, like weight pruning, neuron pruning, and structured pruning. We will explore these in more detail in Section 11.2.1. In the example in Figure 10.2, removing some of the nodes in the inner layers reduces the numbers of edges between the nodes and, in turn, the size of the model.

Quantization: Quantization is the process of constraining an input from a large set to output in a smaller set, primarily in deep learning, this means reducing the number of bits that represent the weights and biases of the model. For example, using 16-bit or 8-bit representations instead of 32-bit can reduce model size and speed up computations, with a minor trade-off in accuracy. We will explore these in more detail in Section 11.3.4. Figure 10.3 shows an example of quantization by rounding to the closest number. The conversion from 32-bit floating point to 16-bit reduces the memory usage by 50%. And going from 32-bit to 8-bit integer, memory is reduced by 75%. While the loss in numeric precision, and consequently model performance, is minor, the memory usage efficiency is very significant.

Knowledge Distillation: Knowledge distillation involves training a smaller model (student) to replicate the behavior of a larger model (teacher). The idea is to transfer the knowledge from the cumbersome model to the lightweight one, so the smaller model attains performance close to its larger counterpart but with significantly fewer parameters. We will explore knowledge distillation in more detail in the Section 11.2.2.1.

10.5 Efficient Inference Hardware

Training an AI model is an intensive task that requires powerful hardware and can take hours to weeks, but inference needs to be as fast as possible, especially in real-time applications. This is where efficient inference hardware comes into play. By optimizing the hardware specifically for inference tasks, we can achieve rapid response times and power-efficient operation, especially crucial for edge devices and embedded systems.

TPUs (Tensor Processing Units): TPUs are custom-built ASICs (Application-Specific Integrated Circuits) by Google to accelerate machine learning workloads (Jouppi et al. 2017). They are optimized for tensor operations, offering high throughput for low-precision arithmetic, and are designed specifically for neural network machine learning. TPUs deliver a significant acceleration in model training and inference as compared to general-purpose GPU/CPUs. This boost means faster model training and real-time or near-real-time inference capabilities, crucial for applications like voice search and augmented reality.

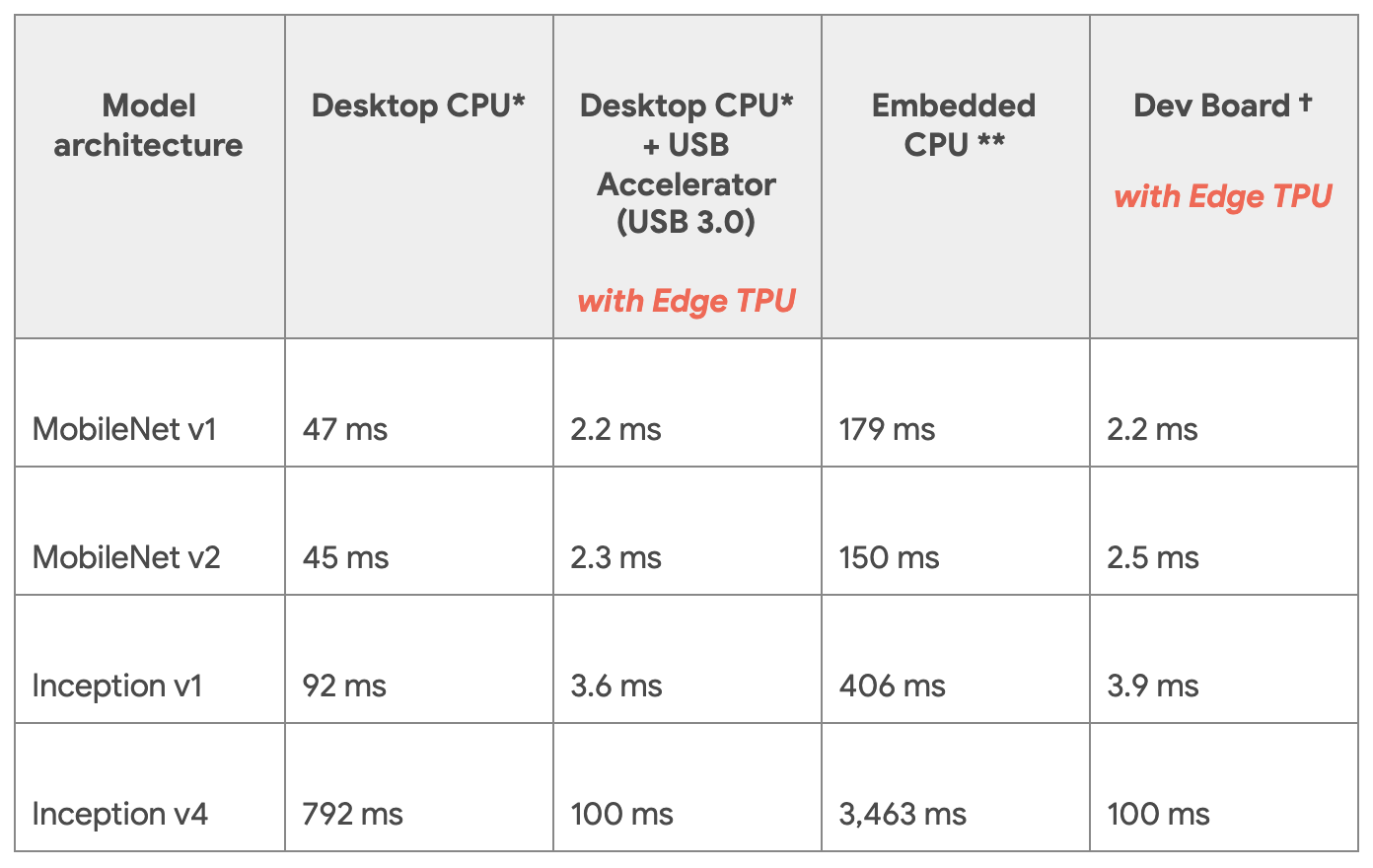

Edge TPUs are a smaller, power-efficient version of Google’s TPUs, tailored for edge devices. They provide fast on-device ML inferencing for TensorFlow Lite models. Edge TPUs allow for low-latency, high-efficiency inference on edge devices like smartphones, IoT devices, and embedded systems. This means AI capabilities can be deployed in real-time applications without needing to communicate with a central server, thus saving bandwidth and reducing latency. Consider the table in Figure 10.4. It shows the performance differences of running different models on CPUs versus a Coral USB accelerator. The Coral USB accelerator is an accessory by Google’s Coral AI platform that lets developrs connect Edge TPUs to Linux computers. Running inference on the Edge TPUs was 70 to 100 times faster than on CPUs.

NN Accelerators: Fixed function neural network accelerators are hardware accelerators designed explicitly for neural network computations. These can be standalone chips or part of a larger system-on-chip (SoC) solution. By optimizing the hardware for the specific operations that neural networks require, such as matrix multiplications and convolutions, NN accelerators can achieve faster inference times and lower power consumption compared to general-purpose CPUs and GPUs. They are especially beneficial in TinyML devices with power or thermal constraints, such as smartwatches, micro-drones, or robotics.

But these are all but the most common place examples, there are a number of other types of hardware that are emerging that have the potential to offer signficiant advantages for inference. These include but are not limited to neuromorphic hardware, photonic computing, and so forth. In Section 12.3 we will explore these in greater detail.

Efficient hardware for inference not only speeds up the process but also saves energy, extends battery life, and can operate in real-time conditions. As AI continues to be integrated into a myriad of applications – from smart cameras to voice assistants – the role of optimized hardware will only become more prominent. By leveraging these specialized hardware components, developers and engineers can bring the power of AI to devices and situations that were previously unthinkable.

10.6 Efficient Numerics

Machine learning, and especially deep learning, involves enormous amounts of computation. Models can have millions to billions of parameters, and these are often trained on vast datasets. Every operation, every multiplication or addition, demands computational resources. Therefore, the precision of the numbers used in these operations can have a significant impact on the computational speed, energy consumption, and memory requirements. This is where the concept of efficient numerics comes into play.

10.6.1 Numerical Formats

There are many different types of numerics. Numerics have a long history in computing systems.

Floating point: Known as single-precision floating-point, FP32 utilizes 32 bits to represent a number, incorporating its sign, exponent, and fraction. FP32 is widely adopted in many deep learning frameworks and offers a balance between accuracy and computational requirements. It’s prevalent in the training phase for many neural networks due to its sufficient precision in capturing minute details during weight updates.

Also known as half-precision floating point, FP16 uses 16 bits to represent a number, including its sign, exponent, and fraction. FP16 offers a good balance between precision and memory savings. It’s particularly popular in deep learning training on GPUs that support mixed-precision arithmetic, combining the speed benefits of FP16 with the precision of FP32 where needed.

There are also several other numerical formats that fall into an exotic calss. An exotic example is BF16, or Brain Floating Point. It is a 16-bit numerical format that is designed explicitly for deep learning applications. It’s a compromise between FP32 and FP16, retaining the 8-bit exponent from FP32 while reducing the mantissa to 7 bits (as compared to FP32’s 23-bit mantissa). This structure prioritizes range over precision. BF16 has been shown to achieve training results that are comparable in accuracy to FP32 while using significantly less memory and computational resources. This makes it suitable not just for inference but also for training deep neural networks.

By retaining the 8-bit exponent of FP32, BF16 offers a similar range, which is crucial for deep learning tasks where certain operations can result in very large or very small numbers. At the same time, by truncating precision, BF16 allows for reduced memory and computational requirements compared to FP32. BF16 has emerged as a promising middle ground in the landscape of numerical formats for deep learning, providing an efficient and effective alternative to the more traditional FP32 and FP16 formats.

Integer: These are integer representations using 8, 4, and 2 bits. They are often used during the inference phase of neural networks, where the weights and activations of the model are quantized to these lower precisions. Integer representations are deterministic and offer significant speed and memory advantages over floating-point representations. For many inference tasks, especially on edge devices, the slight loss in accuracy due to quantization is often acceptable given the efficiency gains. An extreme form of integer numerics is for binary neural networks (BNNs), where weights and activations are constrained to one of two values: either +1 or -1.

Variable bit widths: Beyond the standard widths, research is ongoing into extremely low bit-width numerics, even down to binary or ternary representations. Extremely low bit-width operations can offer significant speedups and reduce power consumption even further. While challenges remain in maintaining model accuracy with such drastic quantization, advances continue to be made in this area.

Efficient numerics is not just about reducing the bit-width of numbers but understanding the trade-offs between accuracy and efficiency. As machine learning models become more pervasive, especially in real-world, resource-constrained environments, the focus on efficient numerics will continue to grow. By thoughtfully selecting and leveraging the appropriate numeric precision, one can achieve robust model performance while optimizing for speed, memory, and energy. The table below summarizes them.

| Precision | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| FP32 (Floating Point 32-bit) | Standard precision used in most deep learning frameworks. High accuracy due to ample representational capacity. Well-suited for training |

High memory usage. Slower inference times compared to quantized models. Higher energy consumption. |

| FP16 (Floating Point 16-bit) | Reduces memory usage compared to FP32. Speeds up computations on hardware that supports FP16. Often used in mixed-precision training to balance speed and accuracy. |

Lower representational capacity compared to FP32. Risk of numerical instability in some models or layers. |

| INT8 (8-bit Integer) | Significantly reduced memory footprint compared to floating-point representations. Faster inference if hardware supports INT8 computations. Suitable for many post-training quantization scenarios. |

Quantization can lead to some accuracy loss. Requires careful calibration during quantization to minimize accuracy degradation. |

| INT4 (4-bit Integer) | Even lower memory usage than INT8. Further speed-up potential for inference. |

Higher risk of accuracy loss compared to INT8. Calibration during quantization becomes more critical. |

| Binary | Minimal memory footprint (only 1 bit per parameter). Extremely fast inference due to bitwise operations. Power efficient. |

Significant accuracy drop for many tasks. Complex training dynamics due to extreme quantization. |

| Ternary | Low memory usage but slightly more than binary. Offers a middle ground between representation and efficiency. |

Accuracy might still be lower than higher precision models. Training dynamics can be complex. |

10.6.2 Efficiency Benefits

Numerical efficiency matters for machine learning workloads for a number of reasons:

Computational Efficiency: High-precision computations (like FP32 or FP64) can be slow and resource-intensive. By reducing numeric precision, one can achieve faster computation times, especially on specialized hardware that supports lower precision.

Memory Efficiency: Storage requirements decrease with reduced numeric precision. For instance, FP16 requires half the memory of FP32. This is crucial when deploying models to edge devices with limited memory or when working with very large models.

Power Efficiency: Lower precision computations often consume less power, which is especially important for battery-operated devices.

Noise Introduction: Interestingly, the noise introduced by using lower precision can sometimes act as a regularizer, helping to prevent overfitting in some models.

Hardware Acceleration: Many modern AI accelerators and GPUs are optimized for lower precision operations, leveraging the efficiency benefits of such numerics.

10.7 Evaluating Models

It’s worth noting that the actual benefits and trade-offs can vary based on the specific architecture of the neural network, the dataset, the task, and the hardware being used. Before deciding on a numeric precision, it’s advisable to perform experiments to evaluate the impact on the desired application.

10.7.1 Efficiency Metrics

To guide this process systematically, it is important to have a deep understanding of model evaluation methods. When assessing AI models’ effectiveness and suitability for various applications, efficiency metrics come to the forefront.

FLOPs (Floating Point Operations) gauge the computational demands of a model. For instance, a modern neural network like BERT has billions of FLOPs, which might be manageable on a powerful cloud server but would be taxing on a smartphone. Higher FLOPs can lead to more prolonged inference times and more significant power drain, especially on devices without specialized hardware accelerators. Hence, for real-time applications such as video streaming or gaming, models with lower FLOPs might be more desirable.

Memory Usage pertains to how much storage the model requires, which affects both the storage and RAM of the deploying device. Consider deploying a model onto a smartphone: a model that occupies several gigabytes of space not only consumes precious storage but might also be slower due to the need to load large weights into memory. This becomes especially crucial for edge devices like security cameras or drones, where minimal memory footprints are vital for both storage and rapid data processing.

Power Consumption becomes especially crucial for devices that rely on batteries. For instance, a wearable health monitor using a power-hungry model could drain its battery in hours, rendering it impractical for continuous health monitoring. As we move toward an era dominated by IoT devices, where many devices operate on battery power, optimizing models for low power consumption becomes essential.

Inference Time is about how swiftly a model can produce results. In applications like autonomous driving, where split-second decisions are the difference between safety and calamity, models must operate rapidly. If a self-driving car’s model takes even a few seconds too long to recognize an obstacle, the consequences could be dire. Hence, ensuring a model’s inference time aligns with the real-time demands of its application is paramount.

In essence, these efficiency metrics are more than mere numbers—they dictate where and how a model can be effectively deployed. A model might boast high accuracy, but if its FLOPs, memory usage, power consumption, or inference time make it unsuitable for its intended platform or real-world scenarios, its practical utility becomes limited.

10.7.2 Efficiency Comparisons

There is an abundance of models in the ecosystem, each boasting its unique strengths and idiosyncrasies. However, pure model accuracy figures or training and inference speeds don’t paint the complete picture. When we dive deeper into comparative analyses, several critical nuances emerge.

Often, we encounter the delicate balance between accuracy and efficiency. For instance, while a dense deep learning model and a lightweight MobileNet variant might both excel in image classification, their computational demands could be at two extremes. This differentiation is especially pronounced when comparing deployments on resource-abundant cloud servers versus constrained TinyML devices. In many real-world scenarios, the marginal gains in accuracy could be overshadowed by the inefficiencies of a resource-intensive model.

Moreover, the optimal model choice isn’t always universal but often depends on the specifics of an application. Consider object detection: a model that excels in general scenarios might falter in niche environments like detecting manufacturing defects on a factory floor. This adaptability—or the lack of it—can dictate a model’s real-world utility.

Another important consideration is the relationship between model complexity and its practical benefits. Take voice-activated assistants as an example such as “Alexa” or “OK Google.” While a complex model might demonstrate a marginally superior understanding of user speech, if it’s slower to respond than a simpler counterpart, the user experience could be compromised. Thus, adding layers or parameters doesn’t always equate to better real-world outcomes.

Furthermore, while benchmark datasets, such as ImageNet (Russakovsky et al. 2015), COCO (Lin et al. 2014), Visual Wake Words (Chowdhery et al. 2019), Google Speech Commands (Warden 2018), etc. provide a standardized performance metric, they might not capture the diversity and unpredictability of real-world data. Two facial recognition models with similar benchmark scores might exhibit varied competencies when faced with diverse ethnic backgrounds or challenging lighting conditions. Such disparities underscore the importance of robustness and consistency across varied data. For example, Figure 10.6 from the Dollar Street dataset shows stove images across extreme monthly incomes. So if a model was trained on pictures of stoves found in wealth countries only, it will fail to recognize stoves from poorer regions.

In essence, a thorough comparative analysis transcends numerical metrics. It’s a holistic assessment, intertwined with real-world applications, costs, and the intricate subtleties that each model brings to the table. This is why it becomes important to have standard benchmarks and metrics that are widely established and adopted by the community.

10.8 Conclusion

Efficient AI is extremely important as we push towards broader and more diverse real-world deployment of machine learning. This chapter provided an overview, exploring the various methodologies and considerations behind achieving efficient AI, starting with the fundamental need, similarities and differences across cloud, edge, and TinyML systems.

We saw that efficient model architectures can be useful for optimizations. Model compression techniques such as pruning, quantization, and knowledge distillation exist to help reduce computational demands and memory footprint without significantly impacting accuracy. Specialized hardware like TPUs and NN accelerators offer optimized silicon for the operations and data flow of neural networks. And efficient numerics strike a balance between precision and efficiency, enabling models to attain robust performance using minimal resources. In the subsequent chapters, we will dive deeper into each of these different topics and explore them in great depth and detail.

Together, these form a holistic framework for efficient AI. But the journey doesn’t end here. Achieving optimally efficient intelligence requires continued research and innovation. As models become more sophisticated, datasets grow larger, and applications diversify into specialized domains, efficiency must evolve in lockstep. Measuring real-world impact would need nuanced benchmarks and standardized metrics beyond simplistic accuracy figures.

Moreover, efficient AI expands beyond technological optimization but also encompasses costs, environmental impact, and ethical considerations for the broader societal good. As AI permeates across industries and daily lives, a comprehensive outlook on efficiency underpins its sustainable and responsible progress. The subsequent chapters will build upon these foundational concepts, providing actionable insights and hands-on best practices for developing and deploying efficient AI solutions.